Where do you find a slam poet, the Vice Mayor of Oslo, the CSO of Mars, and the President of the Marshall Islands in the same room? Well, COP22 of course. But more specifically, at a high-level evening event called “100% Renewable Energy for 1.5°C” hosted by the Climate Vulnerable Forum and the COP22 Presidency.

The event landed in my inbox earlier this week, along with the hundreds of others that bounce around listservs and calendars before not being attended. This one caught my attention because I study renewable energy (RE) as a grad student at the University of Arizona. 100% RE for 1.5 seemed like a great chance to get the round-up version of discussions around RE at COP22.

Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner of the Marshal Islands opened the event with this beautiful poem. I teared up.

Globally, RE needs to expand access and address energy poverty

Rachel Kyte stole the show (well, after the slam poet, obviously). Kyte is the CEO and Special Representative of the UN Secretary General for Sustainable Energy for All, and she lead a powerful visualization exercise. After convincing a packed room of important people to close their eyes, she helped us imagine an alternate reality. “You are a nurse working south of here in Morocco ten years in the future. You come home from your shift knowing that you served your patients well because your clinic has reliable electricity from a micro-grid. Your kids can do their homework at home, and they get a good education because their school is electrified and attracts good teachers who want to work there. You have clean electric cooking at home, and you don’t have that persistent cough your mother carries. You and your children can live with dignity.”

This scenario reminds us that expanding electricity access and addressing energy poverty are a crucial tandem to decarbonizing electricity supply. Just less than one-fifth of the world lives without electricity, and 2.7 billion people don’t have clean cooking fuels. More than 95% of these people live in sub-Saharan Africa or developing Asia, and around 80% are in rural areas. So it’s safe to say that energy poverty remains a huge issue, and expanding electricity access should be a central concern of climate justice work.

I emphasize electricity access because this plays a secondary role in my own research, which focuses on justice questions around energy transition in Tucson, Arizona. Almost everyone in Tucson has access to incredibly reliable, relatively affordable electricity. This doesn’t mean energy poverty isn’t a problem Arizona (many struggle to pay their utility bills and there are thousands unnelectrified homes on the Navajo Nation) but in cities, at least, the U.S. specializes in reliable electricity supply. This isn’t the case for many parts of the world.

Many paths lead to decentralization

Decentralization was a subtext to the event, as it often is in conversations about RE. It made its primary entrance through Stanisals D’Herbemont, a project manager at the REScoop federation representing hundreds of renewable energy cooperatives across Europe. D’Herbemont laid it out plainly:

“We want to put energy back in the hands of citizens. We want people, not just utilities, to share in the profits of renewable energy. We wan’t citizen ownership for the transition.”

My research in Arizona is all about decentralization, in a similar way to the energy cooperatives of REScoop. I’m mostly interested in whether decentralized electricity technologies (like rooftop solar) help catalyze wider political participation of citizens in energy decision-making. Ideally, wider participation means higher public energy literacy and electricity resource planning that benefits ratepayers more than shareholders. As the manager from REScoop summarized, “The result we’ve seen of this decentralization is actually a strong engagement of citizens.” RE is an imperative considering climate change, but it’s also an opportunity to engage people in politics, to shift power from corporations to communities, to decentralize power.

Several panelists said most of the focus within the UNFCCC is on large-scale RE projects, which is usually good for the industrial sector. But, they explained, these projects often don’t expand energy access or improve energy poverty – big issue for less developed countries (LDCs), as discussed above. In rural communities that may never be connected to the electric grid, small RE systems offer an important solution. So decentralization is an important component of RE transition in Africa and the U.S., but generally for very different reasons.

Of course, utility-scale and decentralized RE projects are both part of the solution. The big flagship project at COP22 – only briefly discussed tonight – is the African Renewable Energy Initiative. AREI is an ambitious “Africa-owned and Africa-led” effort to scale up RE across the continent and ensure universal access to energy services. With the goal of delivering 300 GW of new and additional capacity to African grids, you can bet there are some very large RE plants in the line-up.

Transition is inevitable, and so is resistance

I sometimes tell friends that I like studying renewable energy because it’s the positive side of climate change, which can get pretty depressing. While our best effort to agree on global emissions reductions still leads to a terrifying 3.5°C world, the RE industry is taking off. RE accounted for more than half of new electric generating capacity added in 2015, and solar plants have started beating out coal and gas for new power plant bids. RE is one of those rare cases where technology and finance are quickly addressing a global challenge.

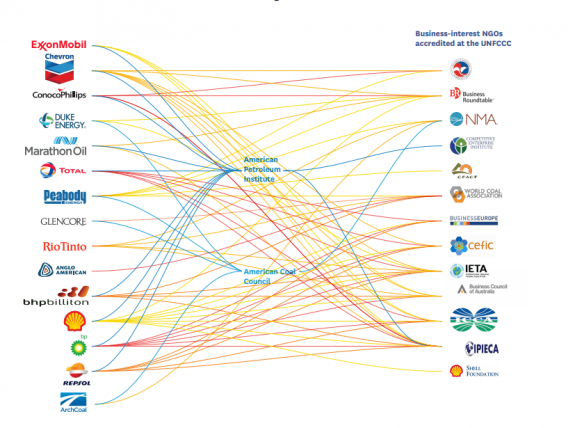

With this evolving market landscape I have no doubt we will see a largely renewable energy world in my lifetime. But as we all know, that isn’t even close to fast enough. Energy transition to stay in line with safe global warming needed to happen five years ago, yet we continue to see massive resistance to RE from the fossil fuel industry. In Arizona this is manifesting in electric utility pushback against policies like net energy metering, which have helped the U.S. rooftop solar industry grow to maturity. At COP22 we see resistance in the major oil, coal and gas companies, which are all at the negotiation table.

India, a young Mauri delegate from New Zealand asked the best question of the night: “How do we achieve 100% renewable energy when fossil fuel companies are sponsoring – and essentially are in bed with – the COP?” The audience applauded this question – perhaps revealing that it’s not just the young activists concerned about conflicts of interests. Unfortunately, only one panelist (an Australian minister) responded, saying that removing subsidies is a crucial first step for governments like Australia. How we elevate this contradiction has been a consistent question for our SustainUS delegation at COP22.

Corporate Accountability International tracks fossil fuel industry access to COP22.

A positive side of neoliberalism?

Reflecting on the evening program as a whole, I can’t help but notice how it nicely fits what we expect from governance under neoliberalism. While there’s a huge literature on this in geography and other social sciences, the TLDR version is that neoliberalism (the 1980s resurgence of laissez-faire economic liberalism, e.g. privatization of public services, deregulation, free trade) is accompanied by certain modes of governance. In particular, neoliberalism tends to involve a ‘hollowing-out’ of the nation state and a shift in power to the local and transnational scales.

Consistent with this theory, the discussion at 100% RE for 1.5°C emphasized solutions at the city, corporate, and trans-national levels. While there were some climate and environment ministers thrown into the mix, the most ambitious RE goals weren’t coming from countries. The Vice-Mayor of Oslo (a former COP youth activist) boasted about the cities incredible RE and transport goals. For example, Oslo’s bus fleet will run only on RE by 2020 and expanded bike lanes mean the city center will soon be entirely closed to vehicles. Chief Sustainability Officers from IKEA and Mars were also at the event; both companies are leading the trend of company’s with formal commitments to 100 RE (for IKEA by 2020). All business representatives who spoke tonight emphasized that RE “just makes sense,” and by that they mean financially. Barry Perkins (CSO of Mars) might as well have been in a SustainUS meeting when he emphasized how “we’ve got to do away with incrementalism.”

In light of last week’s election results, low-carbon energy governance in a hollowed-out nation state makes me feel pretty fuzzy. Even if Trump does pull out of the Paris Agreement and implement every regressive policy we are (vividly) imagining, big companies realize that RE investments are saving them money. As the event moderator joked in her opening, “The pace of renewable energy uptake trumps any other single decision.”